A former British prime minister, Harold Wilson, famously remarked that a week is a long time in politics. But in the world of finance, it seems that everything can change in just two days.

Only 48 hours elapsed between U.S.-based Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) statement on March 8 announcing that it was seeking to raise $2.5 billion (£2 billion) to repair a hole in its balance sheet, and the U.S. regulator Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s announcement that the bank had collapsed.

At its peak in 2021, SVB was worth $44 billion and managed more than $200 billion in assets. Just a week ago it was the 16th largest depository institution in the United States, and now it has become the second largest bank failure in U.S. history. Only the collapse of Washington Mutual during the 2008 global financial crisis was bigger.

Although SVB had been in trouble for some time, the speed of its collapse took almost all commentators, as well as its customers, mostly in the technology sector, by surprise. Tech companies around the world had their cash locked up in SVB deposits and were worried about how they were going to pay their workers and their bills until government support was announced in the U.S., along with HSBC’s agreement to buy SVB’s U.K. arm.

And it appears that the panic against SVB that heralded its collapse – by some metrics, the fastest in history – is spreading to other institutions with similar characteristics. On March 12, two days after SVB’s failure, New York regulators shut down Signature Bank, citing systemic risk.

But was what happened to SVB unforeseeable and inevitable? My research suggests not. My latest book on the history of financial crises, Calming the Storms: the Carry Trade, the Banking School and British Financial Crises Since 1825.was coincidentally published the day before the SVB collapse and describes three situations in which a banking crisis can be triggered.

Why SVB collapsed

One potential cause is when changes in interest rates between countries cause movements in capital flows to start or stop suddenly as investors chase better rates. This affects the availability of financing. This is what happened during the 2007 credit crisis that preceded the global financial crisis, but was not behind SVB’s failure.

SVB’s bankruptcy does relate to the other two situations I describe in my book.

The first is when interest rates rise rapidly. The cause may be a central bank’s reaction to a spike in inflation, a war, or a tight labor market. In fact, the Federal Reserve, along with other central banks, has raised rates from a range of 0.25%-0.5% to 4.5%-4.75% in the last 12 months.

Higher rates tighten credit conditions. This makes it more difficult for financial institutions to finance themselves, while hurting the value of their existing loans and assets.

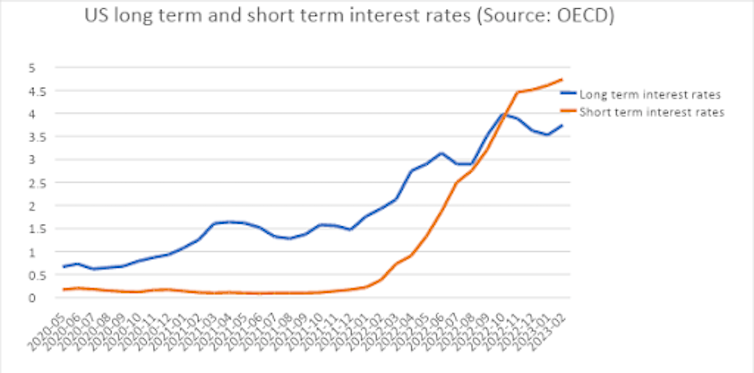

The second occurs when short-term interest rates rise above long-term rates, as has occurred in the United States in recent months. During the pandemic, tech startups with money left over from funding rounds in a world of easy money placed their deposits with the SVB. In the face of weak demand for loans from this sector, SVB invested most of the money in long-term bonds, mainly mortgage-backed securities and U.S. Treasury bonds.

In short, SVB took funds deposited primarily on a short-term basis and tied them up in long-term investments. Then, in recent months, short-term rates rose more than longer-term bond yields (see chart below). This is because interest rates soared, thanks to the Fed’s rate hikes.

Evolution of interest rates in the US.

With rounds of funding harder to come by in a high interest rate environment, technology companies began to withdraw and spend their deposits. At the same time, these higher rates led to a fall in the prices of the bonds in which SVB had been investing. This reduced SVB’s profit margins and put its balance sheet in a delicate situation.

The situation worsened because SVB had to sell some of its longer-term bonds at a loss to fund the deposits its customers were withdrawing from the bank. News of the sales caused depositors to withdraw more funds, which had to be funded by more sales. A vicious cycle ensued.

The March 8 announcement that SVB was trying to raise $2.5 billion to plug the hole in its balance sheet left by these asset sales triggered the banking panic that killed it.

Concerns about systemic risk.

To what extent should we be concerned about the failure of SVB? It is not a major player in the global financial system. It is also unique in modern banking in terms of its dependence on one sector for its customer base and the vulnerability of its balance sheet to interest rate hikes.

But even if SVB’s collapse does not trigger a broader financial crisis, it should serve as an important warning. The rapid rise in interest rates over the past year has fragilized the global economy.

The world’s central bankers are treading a narrow path in trying to combat inflation without damaging financial stability. Central bankers must manage interest rates more carefully, while regulators should discourage the financial sector from borrowing short term to lend long term without sufficient hedging of the risks involved.

It is also important for central banks to monitor the impact that interest rate differentials and cross-border capital flows have on the credit available to both banks and corporates. Even if the SVB and Signature failures turn out to be no more than “small local difficulties” (to quote another former UK prime minister, Harold Macmillan), the systemic risks that their collapse has highlighted can no longer be ignored.![]()

Charles Read, Fellow in Economics and History at Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original.

We recommend METADATA, RPP’s technology podcast. News, analysis, reviews, recommendations and everything you need to know about the technological world.